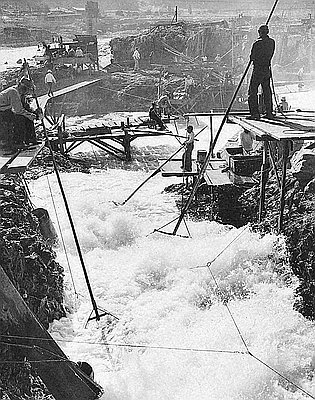

This photograph was taken by Benjamin Gifford around 1900. It shows Indian dipnetters at Celilo Falls fishing for salmon near a fishwheel.

The Dalles-Celilo area was the site of the largest Indian salmon fishery on the Columbia River prior to the construction of The Dalles Dam in the 1950s. The rapid current and rocky banks in this section of the Columbia made it ideal for fishing with dipnets, a type of fishing gear that consists of a pole with a hoop and net attached to one end. Dipnets are dipped into the water and swept downstream by the current, then taken out of the water with a scooping motion. They require whitewater to function so that migrating salmon cannot see the net.

In the 1880s dipnetters began having to compete for prime fishing sites with fishwheels, large fishing devices that used the river current to turn a wheel that caught migrating fish and deposited them in a pen. Like dipnets, fishwheels depend on swift currents to operate. Fishwheels were often placed in the best dipnetting sites, resulting in conflict between Euro-American wheel operators and Indian dipnetters.

The Seufert Brothers Company owned many of the most productive fishwheels on the Columbia. Francis Seufert remembered that his grandfather, also named Francis, was an expert at siting fishwheels. Seufert noted that his grandfather would “take a dipnet, go up along the river and fish along the bank, and when you came to a place where you could dip a lot of salmon from the river, you knew the salmon were there and that was the place to put your wheel.” While the Seuferts generally tolerated Indian fishermen, many of whom sold fish to the Seufert cannery, other fishwheel operators took a more aggressive stance toward dipnetters. Historian Joseph Taylor notes that fishwheel owner I.H. Taffe, who owned the wheel in the photo above, “had a reputation for shooting Indians he caught fishing near his wheels or cannery at Celilo Falls.”

One of the most important cases in Indian case law, U.S. v. Winans, originated from a conflict between Indian fishermen and a fishwheel operator over a fishing site. The case wound its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in 1905 that state fishwheel licenses did not give fishwheel operators exclusive rights to fish at a given location, and that fishwheel operators had to share their fishing sites with Indian fishermen.

Further Reading:

Barber, Katrine. Death of Celilo Falls. Seattle, Wash., 2005.

Seufert, Francis. Wheels of Fortune. Portland, Oreg., 1980.

Taylor, Joseph E., III. Making Salmon: An Environmental History of the Northwest Fisheries Crisis. Seattle, Wash., 1999.

Written by Cain Allen, © Oregon Historical Society, 2006.