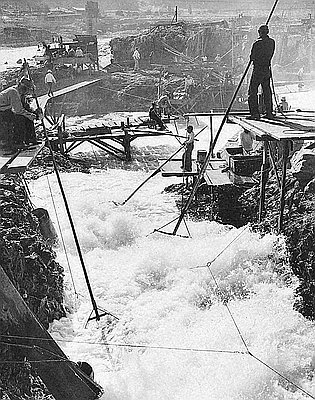

This photograph shows Warm Springs tribal members Edna David (left) and Stella McKinley (right) drying salmon at Celilo Village. It was taken by an Oregon State Highway Travel Division photographer in the early to mid-1950s.

Work was traditionally divided by sex and age among the Native societies of the Columbia River Basin. Men hunted and fished, women and children gathered plant foods and prepared the meat and fish. There were many methods by which women prepared salmon. The photograph above shows how the Wyam, a Native group who lived at Celilo Falls, dried their salmon. The fish were cut into strips and spread out with wooden dowels, then hung in dry sheds. Celilo Falls was an ideal spot to dry fish, as the weather is warm and dry, and the winds that often whip through the Gorge help accelerate the drying process.

Writer Martha McKeown described a drying shed at Celilo Village in 1946:

Fish hang everywhere. Salmon, cut lengthwise into strips a half inch thick to facilitate drying, are spread out like great scarlet fans. The backbone and ribs are also dried, for although little meat adheres to them they are used for soup. The tails are dried. The heads are split and peeled out until they look like huge bat wings….Nothing is wasted, only the entrails are thrown away.

In a children’s book McKeown wrote about Celilo Village, she noted that dry racks were placed north and south “so the clean air from the river will blow between them.”

In 1949 the Bureau of Indian Affairs drew up plans to relocate Celilo Village to the south side of the Columbia River Highway. The chief of the village, Tommy Thompson, wrote a letter to the Oregonian in opposition to the plans. He wrote that the village residents did not want their permanent houses and dry sheds on the south side of the highway as the air currents were “all wrong….The women do all the cutting and drying of fish,” he wrote, “and [are] most unhappy about the south side of highway as fish doesn’t dry and won’t keep.”

The BIA dropped their plans for the relocation of the village, but in 1957 the rising waters of The Dalles Dam forced the village forced to move to the south side of the highway.

Further Reading:

Ackerman, Lillian A. A Necessary Balance: Gender and Power among Indians of the Columbia Plateau. Norman, Okla., 2003.

Barber, Katrine. Death of Celilo Falls. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005.

Written by Cain Allen, © Oregon Historical Society, 2006.