When war broke out, Portland was the only city on the West Coast without a public housing authority, yet it faced the most rapid increase in war workers and the most severe housing shortage in the country. The city council created the Housing Authority of Portland in 1941 to negotiate with the federal government, but it was dominated by private realtors like Chester Moores, who refused to respond to the War Manpower Commission’s request for an estimate of temporary housing units needed for war workers. Because at least 10 percent of the new workers would be black, expanding the area’s black population at least fivefold, Moores and his colleagues feared that their presence would increase the crime rate. When eastside neighbors protested against locating future housing for war workers near them, the Housing Authority refused to act. The Oregonian assumed that the chief of police would be the city’s authority on black newcomers, who would have to find housing in the Albina neighborhood.

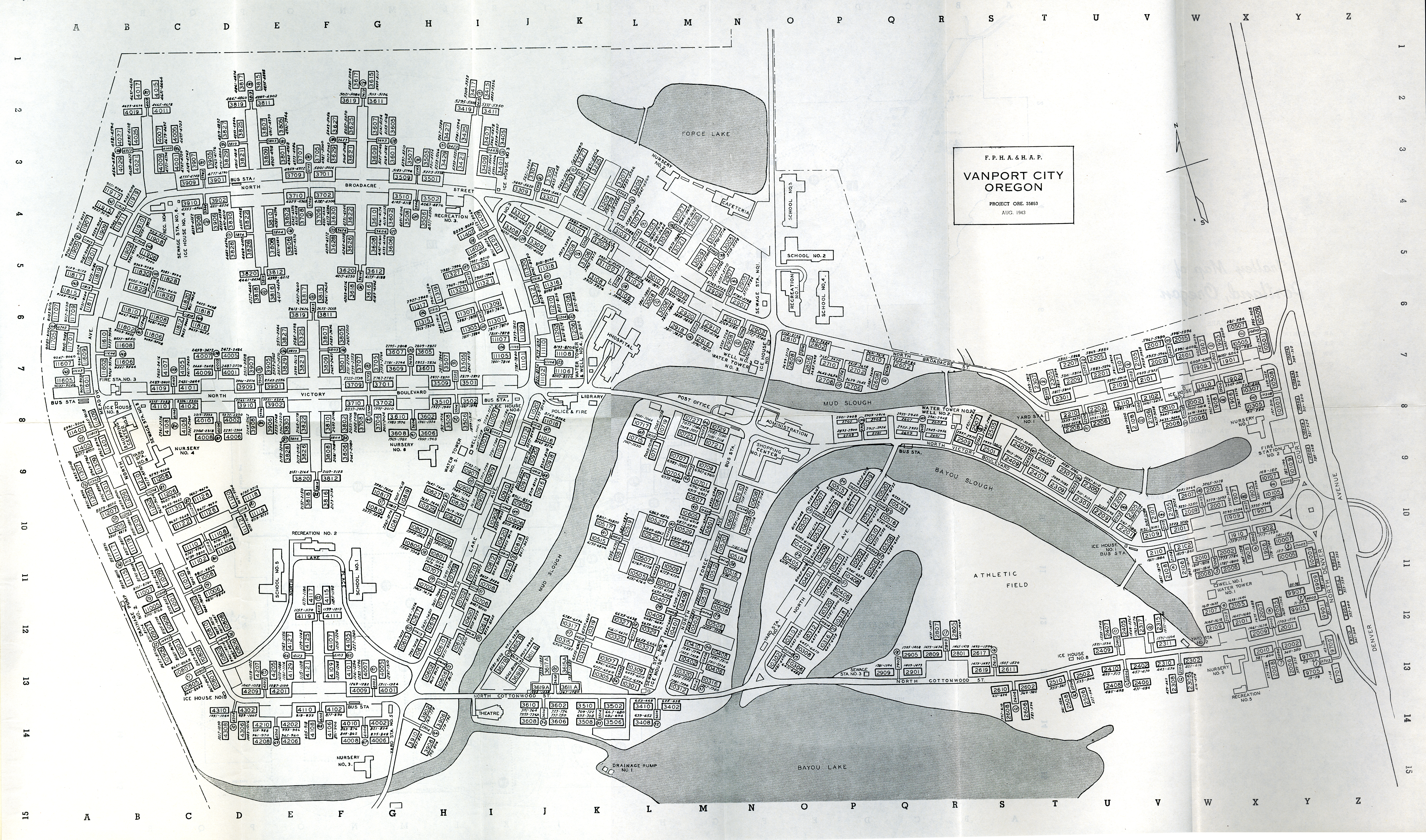

Henry Kaiser, however, could not afford to wait. His company acquired land just north of the city limits between the Columbia Slough and the river’s main channel. The site sat below river level and was protected by a railroad embankment constructed by the Spokane, Portland, and Seattle Railroad in 1907. Kaiser used his influence with federal authorities to acquire building materials, and in August 1942 began construction of the two-story apartment buildings, schools, and recreational centers that would become Vanport. He also created a smaller two thousand unit project at Guild’s Lake, on a portion of the site of the Lewis and Clark Exposition.

With ten thousand units, Vanport became the largest concentration of war housing in the United States. As a temporary city, it was governed by the Housing Authority of Portland, and became the second largest city in Oregon, reaching over 40,000 people in 1944, and settling at 35,000 just after the war. Home construction was deliberately cheap, with hot plates instead of stoves and coal burners instead of electric heating. At least 300 units were constantly vacant because they lacked cooking facilities or furniture. New schools were overcrowded, with four thousand elementary school children in five small buildings attending in two shifts of four hours each. Children from Guild’s Lake families as well as Vanport’s high school students attended Portland public schools, which had many vacant classrooms. Henry Kaiser, anxious to keep his labor force healthy enough to work, also introduced an innovative pre-paid health care system for his workers. Starting with clinics, it gradually expanded to permanent facilities. Until 1996, the Bess Kaiser Medical center was located on Greely Avenue near the former site of the shipyards at Swan Island. As a moral residue, however, the city’s settled middle class identified new shipyard workers with an increase in crime, especially associated with after-hours saloons, gambling, and prostitution. The police, as so often in the city’s history, were perceived as the abettors and benefactors of the rising crime rate.

© William Toll, 2003. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014