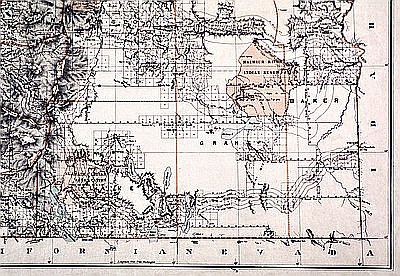

American farming families first began to stream west over the Oregon Trail to the green Willamette Valley in the early 1840s. They followed a well-established route along the Snake River, over the Blue Mountains, and down the Columbia. In 1843, U.S. Army officer John Charles Frémont set off from the Columbia River to explore the area south of the trail. In many instances, Frémont followed the same route first used by Peter Skene Ogden over a decade before.

Frémont’s expedition, riding through a bitter December snowstorm, found and named northern Lake County’s Winter Rim and Summer Lake, and he named Abert Lake for an army superior in Washington, D.C. Frémont was the first person non-Indian to comprehend fully the internal drainage character of the huge area that he explored from 1843 to 1845, a place he named the Great Basin.

Hoping to avoid the difficult Blue Mountains crossing in 1845, a wagon train of Oregon-bound settlers followed their guide, retired trapper Stephen Meek, in search of an easier cut off, up the rugged Malheur River drainage, into the wide Harney Valley, and northwest through the High Desert country. It was a landscape that Meek did not recognize. Without water or feed for the emigrants’ stock, the disgraced guide climbed a butte in desperation and saw the willows of Buck Creek, off in the distance to the north. The trip ended a near disaster, with a number deaths from disease, dehydration, and starvation. In mid October, the survivors limped into The Dalles, on the Columbia River.

The following year—the year that Oregon became U.S. territory—a group of Willamette Valley settlers marked out a new southern alternative to the main Oregon Trail. The Southern Emigrant Road (also known as the Applegate Trail) followed Nevada’s Humboldt River valley, passing well south of southeastern Oregon before it turned north into Oregon to cross the Klamath River. After the Meek’s Cut-off debacle of 1845, almost another decade would pass before the next wagon train crossed the Great Sandy Plains of southeastern Oregon.

Elsewhere in Oregon, development was occurring at an astonishing pace in the mid nineteenth century. Portland, founded in 1845 near the confluence of the Willamette with the Columbia Rivers, had grown into a booming metropolis by 1870. Steamboats plied the Columbia far upstream from the city during the 1860s, and by the end of the decade Portland investors had begun to build a railroad south through the Willamette Valley toward California.

In Southeastern Oregon, the so-called Lost Wagon Train of 1853, led by Oregon settler Elijah Elliott, left the Snake River followed the route of the unfortunate 1845 Meek party for part of the way. In the Harney Valley, Paiute villagers closely guarded their food caches from the hungry emigrants. After a long struggle, Elliott’s wagon train finally made its way through the desert and over the Cascade Range through Willamette Pass into the gentle valley near Eugene. The travelers established a lightly used route for wagons across the High Desert, known as the Free Emigrant Road, much of which is followed today by U.S. Highway 20 in Malheur, Harney, and southeastern Deschutes Counties.

Those years saw increasing conflict between Natives and whites in the region, including Indian raids on wagon trains--such as the so-called Clark Massacre in 1851, in which two emigrants were killed--and emigrants’ attacks on small parties of Indians. As a consequence, relatively few emigrants chose this path to the Willamette Valley during the 1850s. Elsewhere, whites subjugated Native people and forced them onto reservations. The Northern Paiute of southeastern Oregon would soon face the same situation.

From the late 1840s into the early 1860s, small companies of U.S. Army soldiers explored the High Desert. The name of Warner Valley, for example, commemorates an officer killed nearby in 1849; Harney Lake, named in 1859, honored Gen. William S. Harney; and an 1860 military expedition renamed John Work’s Snow Mountain for Maj. Enoch Steen. The successive discoveries of gold during the early 1860s, however, particularly in southern Idaho’s Boise Basin and northeastern Oregon’s Blue Mountains, brought streams of would-be miners from California and western Oregon to the High Desert. Some of them fired on any Indians who came within range of their guns, and the army soon returned to the region with orders to subdue the Northern Paiute once and for all.

Bands of Northern Paiutes occasionally attacked freight wagons hauling supplies from the Columbia River to the John Day mines near Canyon City, and they sometimes rustled a few head from cattle herds being driven from the Rogue Valley to Idaho City and the Boise River mines. Possibly, Northern Paiutes simply considered the cattle and supplies proper payment for travel through their homeland. They also occasionally attacked small parties of would-be miners, both white and Chinese, who were crossing the region to the John Day, Boise Basin, or western Montana gold mines.

As gold mining and settlement spread throughout the Northwest during the 1860s, the army established Fort Harney, Camp Curry, Camp Wright, Camp C.F. Smith, and Camp Warner and proceeded to hunt down Paiutes at every opportunity. Both regular and volunteer Army troops waged the bitter conflict known as the Snake War. Rousted from winter villages, Natives groups had to keep on the run during their annual hunting/gathering season. The pressure of conflict caused some Paiute bands to join together and give their allegiance to war leaders, or chiefs. As the whites killed or captured leaders such as Chief Paulina—who led several central Oregon bands during the mid 1860s and was killed by white settlers in present-day northeastern Jefferson County—the surviving Northern Paiute came under the thumb of the army. Most survivors eventually were placed on the Malheur Reservation, which included a sizable area within the upper drainage of the South Fork of the Malheur River.

When the Northern Paiute were no longer considered a serious threat, the Central Oregon Military Wagon Road was built eastward from the Willamette Valley across the High Desert to Silver City, in the Owyhee Mountains just across the state line in southwest Idaho. The route veered south after crossing the High Cascades at Willamette Pass and passed close by the northern end of Goose Lake, near the site of present-day Lakeview. Having essentially defeated the so-called Snake Indians by 1871, the U.S. government established a 1.8-million-acre reserve, the Malheur Reservation, which occupied much of northeastern Harney and northwestern Malheur counties, for southeastern Oregon's remaining Native people.

© Jeff LaLande, 2005. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.