The Lewis and Clark Expedition is a complex event in American history. The story of the great exploration of the Far West from 1803 to 1806 has been told many times by scholars, essayists, biographers, novelists, and playwrights. Each teller has interpreted events in their own way, seeing the events from different vantage points and emphasizing different themes. This overview is no different. It is written with special emphasis on the time the Corps spent in the Columbia River Basin, in what would become the modern states of Idaho, Washington, and Oregon.

When the Corps of Discovery crossed the Continental Divide on their way west in 1805, they entered a vast region that lay beyond the territories claimed by the United States. They were the first Euro Americans to travel by land into the region and everything they saw and recorded in their journals came as new information to the government, to scientists, and to the public. What they did in the Columbia River Basin, who they met, and how they reacted to what they saw had potential and real impact on subsequent events in Oregon. In a genuine way, the Lewis and Clark Expedition is the beginning of the non-Indian history of Oregon.

Looking back two hundred years on the historic exploration and reconstructing what happened can be difficult and daunting. Fortunately the explorers left minutely detailed journals of their experiences, but there is so much material on what they saw and did that it is overwhelming. The Journals read like extended field reports, with scientific notations clustered alongside a continuous travelogue that is filled with high adventure. We are struck by the relative lack of personal reflection and opinion, but there is little question that the narrative closely adheres to Jefferson’s original aim in sending an expedition to the West—the discovery of what was out there.

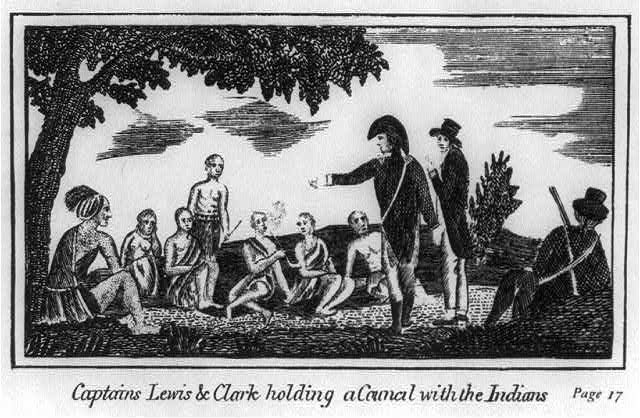

Three major themes run through this overview. First, the Expedition began with Thomas Jefferson’s interest in scientific discovery and the region west of the seaboard continental settlements.The Expedition joined his scientific curiosity with geopolitical goals, particularly the expansion of American interest in the lands west of the Mississippi River.Second, national interest in the western regions was about economic development, natural resource wealth, and commerce. Finding a feasible commercial route across the country, preferably by water, became an expeditionary goal. Third, Jefferson’s strong interest in the West’s indigenous population led him to instruct the captains to take note of the Indian nations and document as much about them and their lives as possible. In addition, the president charged the explorers with establishing trading relationships with all willing tribes.

What the explorers did in the Columbia River Basin in 1805-1806 depended in large measure on their adherence to the Expedition goals and to their abilities, which were considerable. What happened also depended on what they encountered, especially on the attitudes and actions of Native people. The explorers encountered an unknown and surprising region in the Pacific Northwest, and how they dealt with the contingencies they met bore directly on their fortunes as explorers in the Oregon Country.

© William L. Lang, 2004. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.