Women’s work and roles have grown and broadened dramatically since World War II. The number of women working outside the home in Hermiston increased by 60 percent in the 1950s, as men’s employment grew only slightly. By 1960 women constituted more than a third of Umatilla County's paid work force. The growth of employment in government and manufacturing as mining, timber, and farm work declined increased the proportion of jobs open to women.

The area’s politics has become much more conservative since the mid-1960s. But there have been some notable exceptions. Latinos and indigenous peoples have retained many distinctive cultural features, and in the 1960s Latinos began to speak more frequently and assertively about racism. Liberal and radical political viewpoints have become common on the three college campuses—Blue Mountain and Treasure Valley community colleges were founded in the early 1960s. La Grande’s Eastern Oregon University has clubs for students favoring gender equality and Planned Parenthood and for gay, lesbian, bi-sexual, and transgendered people. Tiny Joseph, tucked away in Wallowa County, has become home to many artists.

George Venn, who arrived in La Grande to teach college English in 1970, has long been one of the state’s most respected poets and essayists and emphasizes the importance of place, a sort of countercultural notion in an increasingly mobile and fragmented nation.

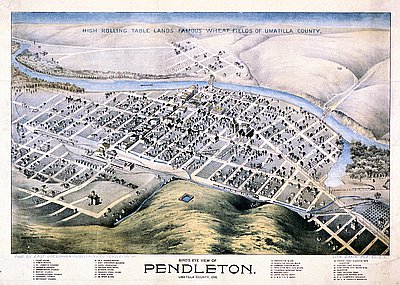

Most of the area’s residents celebrate their past. This is true not only on the Umatilla Indian Reservation, which teaches traditional language, dances, and other elements of Plateau culture, but among whites, too. The Pendleton Round-Up, founded in 1910, is the area’s most popular event, and the Oregon Trail Interpretive Center, outside of Baker City, is its most heralded historic site or museum. Caucasians, rural and urban, commonly identify themselves with rugged pioneers and cowboys.

The area’s high percentage of farmers and laboring men prompted its voters to tilt toward Democratic presidential candidates more than the rest of the state for much of the twentieth century. Northeastern Oregon’s Walter Pierce served as governor from 1923 to 1927 after campaigning for higher taxes on big business and defending working people. This liberal tradition changed by 1968, when Republican presidential candidate Richard Nixon won a strong majority by speaking to the concerns of rural and working people. The mountainous counties have tended to be more politically conservative and distrustful of government than the wheat belt. Support of a 2000 ballot measure stipulating that land owners be compensated for losses due to land-use planning ranged from a high of 72 percent in Wheeler County to a low of 58 percent in Umatilla County—both well above the state average of 53 percent.

Resentment has festered over resource use; many residents believe that ignorant and arrogant urban Oregonians west of the Cascade Mountains wish to breach dams, regulate ranching and farming, restrict the killing of predators, and otherwise threaten their livelihoods. “Portland can vote in anything it wants for the state of Oregon, basically,” complained a rancher in 2003. “Over here we feel like we have no control over our own destiny.”

In 2002 Grant County voters went so far as to ban the United Nations from crossing their borders, as it was reputed to be conspiring to take residents’ land and guns. Like much of the area, Grant County residents both rely heavily on government employment and tend to believe that government regulation has choked their economy.

Oregonians inside and outside of northeastern Oregon continue to debate whether or not government regulation is responsible for the area’s economic decline, whether regulation of logging, mining, farming, and ranching are locking up or preserving precious natural and economic resources. But there is no denying the reality of economic hardship. Northeastern Oregon’s levels of poverty, unemployment, and per capita income compared very unfavorably to the state’s average in 2000, when the gap was widening. The owner of an Ontario hardware store in 2003 painted a grim picture: “So we’re all choking to death. We’re just slowly dying.” That Oregonians in Portland and the Willamette Valley both dominated the state legislature and seemed indifferent to eastern Oregon’s economic problems rubbed salt in the wound.

The area’s icons, rugged pioneers and brave cowboys, seem ill-suited to a modern, global economy of large, multinational corporations, mobile capital, and global competition. This culture of individualism reflects a deeply felt determination to persevere through hard times, even as it also obscures and denies a long legacy of people’s comings and goings to and from a place at the mercy of forces residing outside its borders.

© David Peterson del Mar, 200. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.