In addition to its rich literary heritage, Oregon has a long history of other cultural enterprises. German, Scandinavian, and numerous other ethnic organizations proliferated in the late 1800s. Immigrant groups formed social and ethnic clubs to provide meeting places for Old World celebrations, dances, and other social activities. Some festivals have become popular community celebrations. Since 1961, for example, Junction City’s annual four-day Scandinavian Festival has been devoted to celebrating the foodways, fashions, folk music, and dancing associated with Norway, Finland, Sweden, Denmark, and Iceland. Each August, Junction City’s downtown is transformed with booths, entertainment, glass-blowing demonstrations, and other cultural events.

The small town of Mt. Angel in the Willamette Valley has celebrated an annual harvest festival since 1966. With German sausage, music, craft booths, and dancing in a huge bier garden, the Oktoberfest draws more than 300,000 people to the mid-September event. Astoria hosts a Finnish gala each year, and Portland puts on a Nordic festival.

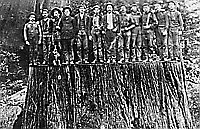

Since the 1940s, the Albany World Championship Timber Carnival has attracted competitors from all over the world to participate in logging skills contests. For four days over the Fourth of July weekend, men and women have competed in climbing, chopping, bucking, and burling contests. Because of smaller crowds and the state’s declining timber economy, the city of Albany discontinued the once-popular carnival in 2002.

Oregon’s cultural establishments include long-standing institutions such as the Oregon Historical Society (established in 1898), the Portland Art Museum (1892), the Columbia River Maritime Museum (1962), the High Desert Museum in Bend (1982), and the Columbia Gorge Discovery Center in The Dalles (1997). New tribal cultural centers include The Museum at Warm Springs (1993) and the Tamástslikt Cultural Institute in Pendleton (1998). The Museum at Warm Springs, designed as a living tribute to the people of the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation, houses tribal artifacts, historical photos, Native material culture, and valuable documents. The Tamástslikt Cultural Institute of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Reservation, located outside Pendleton, was conceived to document and protect the history and culture of the Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla peoples. The private, nonprofit High Desert Museum also has significant Native collections and exhibits as well as exhibits on the natural and cultural heritage of the ION region.

Oregon’s foremost private cultural institution, and the oldest of its kind in the Pacific Northwest, is the Portland Art Museum (PAM). Through the efforts of Henry Corbett, Henry Failing, William Ladd, and C.E.S. Wood, PAM had its beginnings in 1888 as the Portland Art Association. The museum became part of the association’s mission when members signed incorporation documents in 1892 and opened a small gallery in 1895. Through its early years, Portland’s elite loaned collections to the museum for most of the exhibitions. In 1909, the association hired Anna Belle Crocker, who served as museum curator and head of the Museum Art School until her retirement in 1936.

In November 1932, PAM to a new building designed by architect Pietro Belluschi, on Southwest Park and Jefferson Streets. The new museum, which Anna Crocker praised for its “simplicity and convenience,” opened with an exhibit of 750 Japanese prints, the gift of patron Mary Andrews Ladd. During World War II, museum officials sent its most valuable works of art to the interior of the country for safekeeping and operated on a more restricted schedule.

After the war, PAM began hosting large, traveling exhibitions, including paintings from the Walter Chrysler collection, a Vincent Van Gogh exhibit, and single-person shows for regional artists. The board initiated its first capital campaign in 1967 to build a new wing, classroom and studio space, and an auditorium. The new wing, another Pietro Belluschi design, opened in 1970. A few years later, the museum began its long association with Vivian and Gordon Gilkey and their collection of print works. In 2005, PAM opened a new wing dedicated to the Center for Modern and Contemporary Art.

One of the most distinguished of the state’s musical institutions is the Oregon Symphony Orchestra, whose lineage can be traced to the founding of the Portland Symphony Society in 1896, the first of its kind in the American West. Between 1911 and 1918, the symphony made the transition to a modern professional organization and performed its first concert in Portland’s new Civic Auditorium in 1918. Although it ranked as one of the nation’s largest orchestras at the beginning of the Great Depression, the economic collapse of the 1930s forced the suspension of concerts in 1938, leaving Portland without an orchestra until 1947, when the Society was reorganized.

Because of its growing commitment to serve communities beyond Portland, the Society changed its name to the Oregon Symphony in 1967. The appointment in 1980 of James DePriest as music director and conductor, recognized in the United States and Europe for his symphonic repertoire, elevated the symphony to still higher professional standards. Shortly after DePriest assumed his position, the symphony moved from Civic Auditorium to the Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall, where the orchestra could rehearse and perform on the same stage. With De Priest’s retirement in 2002, the symphony hired Carlos Kalmar, music director of Vienna’s Tonkunstlerorchester and the Anhaltisches Theater in Dessau, Germany.

During the twentieth century, music festivals became part of Oregon’s performance scene. The Britt Festivals in southwestern Oregon had its beginnings in 1963 when Portland conductor John Trudeau and Sam McKinney visited Jacksonville and saw the hillside where photographer and orchardist Peter Britt had first settled in Oregon in 1852. Within months, Trudeau was conducting a small chamber orchestra for an audience on the hillside. The Britt Festivals performed only classical music during its first years, but it has broadened its offerings to embrace jazz, gospel, rock and roll, and other styles of music. Currently operated by Jackson County, Britt Park attracts world-class performers and can accommodate as many as 2,200 people.

Several summer music festivals have been held in Oregon since the 1960s. The Mt. Hood Jazz Festival, for example, began in 1982 in Gresham, east of Portland. In 1987, the first Rose City Blues Festival was held in Portland’s Waterfront Park, and the Portland Jazz Festival began its annual festival in 2004. The Oregon Bach Festival originated in a partnership between organist and conductor Helmuth Rilling and Royce Saltzman of Eugene. In 1971, the two men collaborated to create the Summer Festival of Music in Eugene; the performances were renamed the Oregon Bach Festival in the late 1970s. In the twenty-first century, the event attracts internationally known artists and more than thirty thousand people to the annual festival.

Ashland is renowned for its highly acclaimed Oregon Shakespeare Festival and repertory theater company. In the 1890s, Ashland opened its first beehive-like Chautauqua dome. City boosters constructed Chautauqua domes in 1905 and 1917 and its first outdoor Elizabethan stage in 1935. That same year, Angus Bowmer produced the first Shakespeare play, the beginning of a festival that would earn a national and international reputation. The festival presents plays on the outdoor, 1,200-seat Elizabethan theater; the Bowmer Theater, built in 1970; and the small Black Swan Theater, opened in 1977. Remnants of the Chautauqua beehive provide the perimeter walls for the festival’s outdoor theater. The Oregon Shakespeare Festival attracts more than 340,000 each year.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.