Although Oregon gained national attention as an environmental pacesetter during the early 1970s, the state had a long history of using its waterways as municipal and industrial dumping grounds. As early as 1907, the newly created Oregon Board of Health referred to the Willamette River as “an open sewer,” a characterization that would fit the waterway for several decades. A Portland City Club study in 1927 called the river “filthy and ugly.” In 1938, a successful initiative measure supported by the Stream Purification League and the Isaak Walton League, established the Oregon Sanitary Authority.

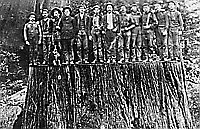

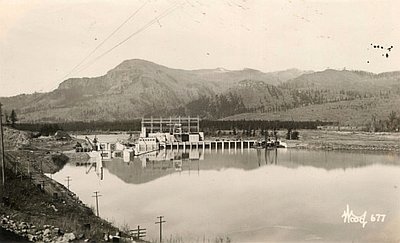

Despite the new enforcement agency, legislators dragged their feet, municipal governments procrastinated in installing primary sewage treatment facilities, and industries continued to dump indiscriminately into the river. While efforts to clean up the river were put on hold during World War II, a major flood in 1948 spurred the construction of several multi-purpose dams known as the Willamette Valley Project. The federal Clean Water Act of 1948 forced the City of Portland to build a modern sewage treatment plant. In 1950, the Sanitary Authority set its first deadline requiring pulp mills to cease dumping waste into the river.

By the 1960s, the Willamette River had become the center of intense politicking, especially with the emergence of two progressive political figures, State Treasurer Robert Straub, a Democrat, and Secretary of State Tom McCall, a Republican. McCall had been a television reporter and commentator on KGW-TV in Portland, and he had paid attention to pollution issues, especially those affecting the Willamette River. On November 12, 1962, KGW aired McCall’s documentary, Pollution in Paradise, a sharply critical report of the condition of the Willamette. In the film, McCall staked out a moral position in the pollution debate and brought attention to issues of livability in the state. Pollution in Paradise was a tour de force, pressing home the idea that there was no contradiction between jobs and quality of life in Oregon.

More than any of Oregon’s elected officials since World War II, Tom McCall helped forge a modern identity for the state. As a student at the University of Oregon during the Depression years, McCall had become acquainted with Richard Neuberger, who would become one of the region’s most prominent journalists and a future U.S. senator (1954-1960). The dean of the university’s law school during McCall’s undergraduate years was the brilliant and outspoken Wayne Morse, who would serve in the U.S. Senate from 1945 until 1969.

As McCall worked his way into Republican Party politics, he served a stint as executive secretary to Governor Douglas McKay in the late 1940s and made a failed attempt in 1954 to win the third congressional district seat. Democrat Edith Green defeated McCall by a narrow margin in that election and went on to serve ten terms in the House of Representatives. McCall’s position as a television commentator helped elevate him to the secretary of state’s office in 1964 and then to the pinnacle of Oregon politics in 1966 when he was elected governor in a successful campaign against Bob Straub.

It would be an understatement to say that McCall brought a different style, a flair for imaginative expression, to the governorship. His two terms in the governor’s office were fortuitous, paralleling significant improvements in water quality in the Willamette River and the completion of the last Willamette Valley Project dams. McCall also appointed himself interim chair of the State Sanitary Authority, threatening to shut down pulp and paper mills unless they cleaned up their businesses and creating the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) with expanded statutory responsibilities. While he shares credit for several wide-ranging environmental achievements, it was the Willamette River that brought the governor to national attention.

The several dams on the Willamette River system, built between 1940 and the 1960s, helped reduce pollution, especially in the Portland Harbor, and provided a technological fix to a persisting problem. Tributary dams store seasonal precipitation, which is released during the summer and autumn months to maintain a relatively even flow in the main river—a procedure that flushes contaminants downriver. In addition, the water impounded in the reservoirs keeps most seasonal flooding from farmland and the valley’s major cities.

While a 1972 article in National Geographic praising McCall for his cleanup of the river is well deserved, an important and seldom mentioned factor in the pollution story is the regulated flow of the river. The mushrooming growth of Willamette Valley cities and suburbs and the massive introduction of chemicals into the environment since World War II have contributed to other problems in the basin. The Willamette River—perhaps Oregon’s miner’s canary—began producing deformed and disfigured fish in the lower stretches of the waterway. What Oregon had accomplished in its 1970s cleanup of the Willamette River was the elimination of point-source pollution, the most readily identifiable type of pollution flowing from sewers and pipes.

Nearly two decades passed before the condition of the Willamette River again made headline news. Then reports of troubled waters came with a rush. First, Governor John Kitzhaber’s 1997 task force reported findings of petroleum residues, toxic chemicals, and metal byproducts in urban areas and pest and nutrient contaminants in rural sections of the river. The report emphasized that nonpoint source pollution entering the stream during months of high precipitation far exceeded point-source contaminants and that urban areas contributed a far higher pollutant load per acre than rural lands. In 1999, the National Marine Fisheries Service invoked the Endangered Species Act and listed nine Northwest fish populations as threatened. One year later, the hammer fell again when the Environmental Protection Agency designated a large section of Portland Harbor a Superfund cleanup site.

In a sense, the past was coming home to roost, and the long history of Portland’s industrial connection to the Willamette River was being played out in messy, confrontational forums. City commissioners dueled with Governor Kitzhaber when he questioned Portland’s resolve to deal with its sewage problems, and fingers were pointed upriver and downriver and between rural and urban politicians. The Oregonian defended Portland’s efforts and accused the DEQ of sticking it to the city “with what can only be imagined as the governmental equivalent of glee.” In 1997, the City of Portland began work on what became known as the Big Pipe. The project was completed in 2011, after constructing the sections of the Big Pipe on the west and east sides of the city. The project was the result of a 1995 circuit court decision that required the city to end the combined sewer outflow system and isolate sewage from runoff water.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.