When John McLoughlin visited the Willamette Valley in 1832, he remarked that it deserved “all the praises Bestowed on it as it is the finest country I have ever seen.” Bounded by the Coastal Range, the Cascade Range, and the Calapooya Mountains, and extending from present-day Portland to Eugene, the valley measures one hundred miles long and twenty to thirty miles wide. It was home to the Kalapuyans—the Tualatin-Yamhill Kalapuyans in the north, the Santiam-McKenzie in the central and south, and the Yoncalla in the south, into the Umpqua Valley. Anthropologists estimate that at its peak the Kalapuyan population reached 13,500 people. The Kalapuyans moved seasonally to different parts of the valley, gathering plants, hunting wild game and fowl, and manipulating the environment through fire to increase the availability of certain foods and resources. They were greatly affected by contact with diseases such as smallpox and malaria, which were introduced to the valley by fur traders and immigrants in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. By 1844, only three hundred Kalapuyans had survived. A decade later, the remaining Kalapuyans were forced to cede their lands in the Willamette Valley to the United States government./

To the south, along the Willamette River in French Prairie, former employees of the North West Company and HBC, including sizable numbers of French Canadians, were establishing rudimentary farmsteads and raising a few livestock. At Fort Vancouver, McLoughlin reported in a lengthy letter to HBC officials in November 1834, Boston merchant Nathaniel Wyeth had arrived, in addition to Methodist missionaries Jason and Daniel Lee and naturalists John Kirk Townsend and Thomas Nuttall.

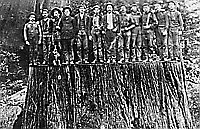

These and other newcomers were beginning the slow and difficult work of imposing a new order on the Willamette Valley landscape. They brought with them animals and plants—cattle, pigs, sheep, wheat, and grafted cherry, apple, and pear trees—that were especially well adapted to the climate. The Americans on their way to the Oregon Country during the 1830s was the vanguard of what would become a flood of overland immigrants to the Willamette Valley in the 1840s, and to the Umpqua and Rogue valleys to the south during the next two decades. During those years and into the 1860s and 1870s, Native groups were increasingly pushed to the margins through federal treaties that established reservations, most of them far from traditional homelands.

Why did they come, these people from the East and the Midwest? What prompted such great numbers of people to travel nearly two thousand miles to find new homes? The interest in the Oregon Country was a result of the convergence of events and circumstances that gathered momentum in the aftermath of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and especially the War of 1812. In 1818, Great Britain and the United States settled agreed to the 49th Parallel as the northern boundary of the Oregon Country, but both nations’ interest in Oregon prompted negotiators to establish a Joint Occupancy of the region. In essence, the treaty symbolized the contest between an ambitious and expanding American nation and a diminishing European presence in North America.

The Americans were also becoming more aggressive in their ambitions. On April 15, 1824, a select committee of the U.S. House of Representatives on the “expediency of occupying the mouth of the…Columbia” issued a flattering and exaggerated report, which concluded that “both in a military and commercial point of view, the occupation of that territory is of great importance to the Republic.” Singled out for praise was the area’s proximity to China, its lucrative fur trade, its agricultural potential, and its excellent fisheries. Thomas Hart Benson, Missouri’s senator in Congress and the editor of the St. Louis Enquirer, urged the occupation and settlement of the Oregon Country. With the publication of the House report, Benton, wrote in Thirty Years’ View (1858): “the first blow was struck: public attention was awakened, and the geographical, historical, and statistical facts set forth in the report, made a lodgment in the public mind which promised eventual favorable consideration.” For nearly two decades, Benton and others described the Northwest as an earthly paradise, a place where prudent and ambitious American citizens could turn their dreams to reality.

Others were even less hinged to reality. The most single-minded and obsessive of the Americans promoting settlement on the Columbia River was Harvard-educated Hall Jackson Kelley. After reading the Lewis and Clark journals in 1817, Kelley promoted the Oregon Country as a “New Eden,” a land with “sublime and conspicuous” mountains and a “salubrious” climate that was “well watered, nourished by a rich soil, and warmed by a congenial heat.” Kelley publicized Oregon in letters to major eastern newspapers and in A Geographic Sketch of that Part of North America Called Oregon (1830), a wildly imaginative pamphlet plagiarized from earlier journals. He put his promotional talents to work in Boston when he established a society to encourage the establishment of Christian settlements on the Columbia River. While historians have ridiculed Kelley as eccentric and out of touch with reality, Boston entrepreneur Nathaniel Wyeth, who made two abortive efforts to establish business enterprises on the Columbia, was a member of his society. Presbyterian missionary Henry Harmon Spalding, who in 1836 would build a mission house and school at Lapwai in present-day Idaho, was also a member of Kelley’s group.

Missionaries greatly aided in disseminating information about the Northwest, especially in their favorable descriptions of the agricultural potential of places such as the Willamette Valley. Published in religious journals, missionary reports praised the prospects of a promised land and offered visions of a limitless future. From the vantage of the Waiilatpu mission in the Walla Walla Valley in present-day southeastern Washington, Marcus Whitman praised the region’s fertile soil, its “mild equable climate,” and its superior “advantages for Manufactories and Commerce.” Although Protestant mission organizations commissioned the Marcus and Narcissa Whitman, Henry and Eliza Spalding, and Jason and Daniel Lees to convert Indians to Christianity, their greatest efforts were directed toward urging white settlement of the region. As John McLoughlin wrote in 1847, “It always seemed that the great influx of American missionaries and the statements of the Country these missionaries sent to their friends circulated through the United States in the public papers were the remote cause” of white settlement.

There was more to the emigrant movement to the Northwest than the overblown descriptions of the region. People have always made decisions about migrating to new lands based on certain assumptions and values, and most population movements in nineteenth-century America followed in the wake of shifting social and economic conditions. “Motive,” geographer William Bowen has argued, “is fundamental to migration.” Moreover, motivation becomes increasingly important the more distant and difficult the move. Until the 1840s, there were only a few isolated Euro-American settlements in the Columbia country—Fort Vancouver and its scattered outposts, former HBC trappers in the French Prairie area, and missions in the Willamette Valley and the interior. A series of circumstances during the 1830s and 1840s, however, irrevocably altered the settlement pattern in the Oregon Country. On the receiving end of the Edenic stories about Oregon, especially in the American Midwest, were farmers suffering from a floundering agricultural economy and a prolonged period of depressed prices in the wake of the Panic of 1837.

Scholars have deliberated about the factors that contributed to the “Oregon fever” of the 1840s. Geographer William Bowen discounts the themes often recited in Fourth of July speeches that credit the patriotic idealism of immigrants and their “inspired nationalism” to win Oregon from the British. He was inclined toward a more conventional list of motives: the lingering effects of the Panic of 1837; several years of flooding in Missouri, Iowa, and Illinois; the lure of free land; the promise of economic betterment; the quest for adventure and excitement; and the promise of physical health. Chronic sickness and disease in the Mississippi Valley, Bowen concludes, rank ahead of economic considerations and all other factors as motives for people moving to Oregon. Other scholars, including historian Carlos Schwantes, argue that agrarian societies equate wealth with landholding and that hard-pressed midwestern farmers found the promise of abundant and fertile land a sufficient attraction to undertake the arduous two-thousand-mile journey to the Willamette Valley.

They came with a rush. During his reconnaissance of the Oregon Country in 1841, Charles Wilkes estimated a population of between 700 and 800 “whites, Canadians, and half breeds.” Of that number, about 150 were Americans, most of them associated with the mission settlements at Willamette Falls and farther up the valley. By the early 1840s, HBC personnel who had lived in the region for nearly two decades were amazed at the number of overlanders suddenly in their midst. A company trader at Fort Nez Perces on the Walla Walla River reported that the Americans were getting “as thick as Mosquitoes in this part of the world.” When the large immigrant group known as the Great Migration arrived in the Willamette Valley in 1843—approximately nine hundred people from Missouri and the Ohio and Mississippi Valleys—McLoughlin expressed alarm that the country was “settling fast.”

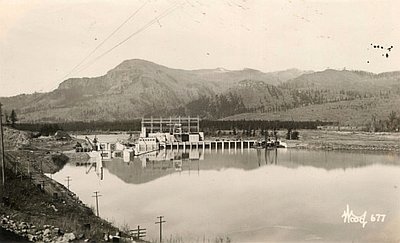

The growth of Oregon City provides an example of the transformation taking place in the valley. Two years after McLoughlin established a land claim at Willamette Falls in 1829, the HBC opened a sawmill at the site. The Methodists then established a mission at the falls, and the settlement grew from a single building in 1840 to several more early in 1843. The newly named Oregon City had seventy-five structures by the close of the year. In the New York Weekly Herald in 1844, Peter J. Burnett reported that the settlement had four stores, two sawmills, one gristmill, and another under construction. “There is quite a little village here,” he wrote. When Joel Palmer arrived in 1845, he reported that Oregon City had taken on the appearance of a village of about a hundred houses, “most of them not only commodious, but neat.” The town had three hundred residents, two conspicuous public buildings—a Methodist church and a Catholic chapel—and the usual array of services.

With only a remnant of the Kalapuyan people still living in the Willamette Valley, the newcomers experienced little resistance as they staked out generous land claims for themselves. Euro-American population increased considerably in the Willamette Valley from 1843 to 1860: to 1,500 in 1843; 6,000 in 1845; 9,083 in 1849; 13,294 in 1850; and 52,000 in 1860. It is nearly impossible to estimate Oregon’s Native population based on the first territorial census in 1850. The Bureau of the Census distributed confusing instructions about counting Indian people, and their populations were in sharp decline. In the Willamette Valley, geographer William Bowen estimates a Kalapuya population of 500 people.

Until the settlement of the boundary issue in 1846, John McLoughlin directed most Americans south to the Willamette Valley, with only a few immigrants pushing north into the Cowlitz Valley and the southern tip of Puget Sound. With the increasing number of American citizens in their midst, HBC officials tried to attract Canadians to settle the area north of the Columbia River. The company also invited Roman Catholic missionaries to counter the influence of the Protestant missions. With canoes and provisions supplied by the HBC, two Franciscan priests from Canada, Francis Norbert Blanchet and Modeste Demers, arrived in the Oregon Country in 1838 and marked the beginning of Catholic missionary work in the region. The two missionary groups were at odds, in large part because of their differing religious beliefs. In addition, some Catholic missionaries suspected the Protestants of using the guise of religion to promote trade and commerce in the Oregon Country.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.