Oregon’s social and cultural life during the 1920s reflected the conventions of a largely homogeneous society, with tendencies toward social, cultural, and religious conformity. Those characteristics suggest in part the geographic isolation of the Pacific Northwest and the welter of changes that followed World War I. The war, according to writer Malcolm Clark, marked “a generation of changes…compressed into 18 months.”

The woman’s suffrage and Prohibition amendments were added to the U.S. Constitution, and discussions about sex emerged from the closet to become a part of everyday conversation. Added to those changes were anxieties associated with the triumph of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia in 1917, the emergence of U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer and the “Red Scare” of 1919, and the region’s faltering agricultural and lumber economy. Many conservative and traditionally minded Oregonians ascribed those disruptions to the increased acceptance of unrestricted and licentious behavior.

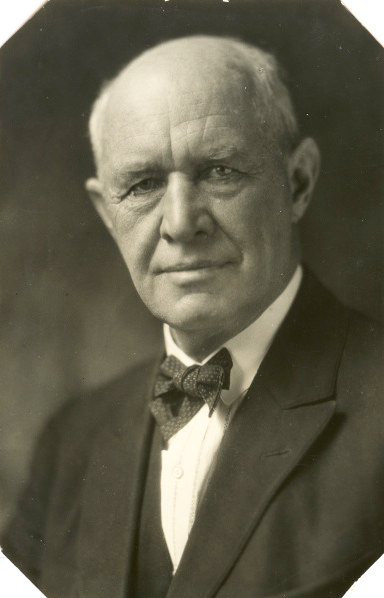

In the social and economic turbulence that followed the war, Oregon’s homogeneous population appeared to be ready recruiting ground for groups appealing to white, Anglo Saxon, Protestant values, with symbolism vested in the Bible, the flag, and patriotism. The American Protective Association and the Ku Klux Klan, claiming to be guardians of American institutions and values and opposed to Roman Catholicism and race-mixing, made rapid strides in Oregon during the early 1920s. Klan recruiters arrived in 1921, and within two years the organization had helped elect eastern Oregon Democrat Walter Pierce to the governorship. (In this and subsequent elections, Pierce was notably silent on the Klan issue.)

Appealing to its own narrow brand of ethnic, racial, and religious bigotry, the Klan dominated the state legislature and helped elect Klansman Kaspar K. Kubli speaker of the House. The Klan enjoyed fairly widespread support for its conservative social agenda and was most effective in promoting it through the direct-legislation process. Its most significant effort was the Compulsory School Bill, a 1922 initiative originating from the Scottish Rite Masonic Order that would have eliminated parochial and private schools by requiring children between the ages of eight and sixteen to attend public schools. Although voters approved the measure 115,506 to 103,685, the state supreme court declared the law unconstitutional; the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the ruling in 1925.

Under the Klan’s influence, the Oregon legislature passed the Alien Land Act in 1923, a statute prohibiting aliens from owning or leasing land. The measure as directed at immigrant Japanese in Portland and the Hood River valley; at the time, 4,077 Japanese lived in Oregon, 60 percent of them working in agriculture. Similar laws passed in Washington and California—and were upheld in the courts.

With Governor Pierce’s support, the same legislative session banned sectarian clothing in public schools and petitioned Congress to restrict Asian immigration to the United States. Although the sentiments that the Klan appealed to continued to be part of Oregon’s political fabric, its national and state membership declined as precipitously as it had risen. As for Walter Pierce, he went on to serve five terms in the U.S. House of Representatives as a public-power advocate and supporter of the New Deal.

© William G. Robbins, 2002. Updated and revised by OE Staff, 2014.